This insight and project certainty assessment is excerpted from our pending hydrogen country reports, which form part of Westwood’s new Hydrogen solution, coming soon. For more information or to speak to a specialist, please contact [email protected].

To access a PDF copy, please provide your email address below:

Introduction

In 2022, the EU unveiled its REPowerEU plan that set a target for 10Mtpa of domestic hydrogen production and 10Mtpa of hydrogen imports by 2030. This represented a significant increase from the original 5.6Mtpa target set by the preceding ‘Fit for 55’ package. REPowerEU was aimed at rapidly reducing the EU’s dependence on Russian fossil fuels following the war with Ukraine.

Given this ambitious target, several countries have announced import initiatives. With significant growth expected in hydrogen demand in Northwest Europe, the Netherlands and Belgium announced ambitions to become hydrogen import hubs for Europe – not just for their own domestic needs, but also for neighbouring EU countries. The question is: can they deliver? This Insight explores whether there is room in the game for both countries to play leading roles in Northwest Europe, and to what extent they are able to meet Europe’s hydrogen import target by comparing their capabilities and initiatives in this space.

The Netherlands and Belgium’s combined import targets can meet up to 62% of the EU’s 10Mtpa hydrogen import target.

Figure 1: Hydrogen Import Targets for 2030 – The Netherlands and Belgium vs EU. Source: Port of Rotterdam, Port of Amsterdam, Port of Antwerp-Bruges and REPowerEU

The Netherlands announced hydrogen import targets for 2030 at two of its largest ports – Rotterdam (4.6Mtpa) and Amsterdam (1Mtpa); the target at Rotterdam increases to 18Mtpa by 2050.

Belgium has a much smaller import target of 0.6Mtpa, which will be centred around its Port of Antwerp-Bruges. Despite this seemingly conservative target, the country stands ready to take the necessary steps for the promotion of hydrogen today, as highlighted by its early adoption of its Hydrogen Act ahead of the EU. Belgium’s potential can be expanded in the future, especially if it develops its pipeline to connect with southern Europe (i.e. the Iberian peninsula) as part of the European backbone initiative, which is the country’s longer-term ambition.

Nevertheless, these two countries together could supply up to 62% of the EU’s 10Mtpa hydrogen import target for 2030, leaving a 3.8Mtpa gap to be supplied from other countries.

This suggests there is adequate demand for both the Netherlands and Belgium to play a central role, but this also depends on Germany, which is likely to be another key importer in Northwest Europe. Germany intends to be a large consumer of hydrogen and has set a 10GW hydrogen production target for 2030. In its revised hydrogen strategy, the German government states it expects the majority of hydrogen demand to be met by imports from both EU and third-party countries. Germany is progressing plans to import hydrogen in the form of ammonia into Wilhelmshaven and receive hydrogen via pipeline from its EU neighbours.

Sufficient risk remains in the Netherlands’ and Belgium’s hydrogen project pipelines, potentially necessitating hydrogen imports to meet their own domestic needs.

The Netherlands and Belgium rank as Europe’s 7th and 8th largest emitters, respectively. Both countries have large energy-intensive industries to decarbonise. Despite a strong pipeline of hydrogen projects, particularly in the Netherlands, there remains sufficient risk to suggest that not all announced projects will be realised, in which case domestic hydrogen production may be insufficient and imports required to meet each country’s decarbonisation goals.

For instance, the Netherlands announced 12.5GW of hydrogen capacity (blue and green) to come online by 2030, which is 2-3x larger than the country’s 3-4Mtpa 2030 target. If the project pipeline were fully realised, then clearly this target could be easily met; however, Westwood believes there is sufficient risk to suggest that not all the announced capacity may come online.

Figure 2: Westwood’s Project Certainty Assessment of the Netherlands’ hydrogen production capacity pipeline vs country target. Source: Westwood analysis

The above chart is taken from Westwood’s Hydrogen Project Certainty analysis, in which a project is assessed using a consistent set of criteria to ascertain the risk – and therefore likelihood – of a project reaching final investment decision (FID). Projects are categorised as ‘Probable’ (low risk), ‘Possible’ (moderate risk) or ‘Risked’ (high risk).

Our analysis suggests 3Mtpa of projects are ‘Probable’ by 2030. If considering a 4GW target, an additional 1GW of project capacity would still need to be commissioned. This increases to 5GW if the Dutch government ratifies the 8GW target that has been proposed for 2032.

72% of the Netherlands’ 12.5GW pipeline are green hydrogen projects and mostly coastal; of this, 92% require power from offshore wind. Therefore, meeting the country’s offshore wind target will be crucial to meeting its hydrogen target. While Westwood expects that the Netherlands will largely meet its offshore wind target, energy demand for electrification is likely to compete with energy for green hydrogen projects. If the green hydrogen projects cannot secure the required electricity at an adequate cost, hydrogen projects may struggle to reach FID. In this scenario, hydrogen imports can bridge any shortfall in production and keep the country on track towards reaching its decarbonisation goals.

The Netherlands and Belgium are well-positioned to become key hydrogen import hubs.

According to both countries’ hydrogen roadmaps, early hydrogen imports will be consumed domestically, particularly for industrial decarbonisation; however, both roadmaps have set targets for an increase in hydrogen imports specifically for Europe. There is a strong opportunity for the Netherlands and Belgium, which benefit from being located geographically nearby Germany, and as previously noted, has a large hydrogen import requirement. Both countries have specified Germany as a key target country for its hydrogen imports and are expanding their infrastructure to supply Germany and other European destinations from the late 2020s.

The Netherlands and Belgium each host one of Europe’s two busiest ports – Rotterdam and Antwerp. These ports have existing infrastructure that can be leveraged and/or repurposed for the import and distribution of hydrogen and its derivatives, including terminals, gas processing facilities, storage tanks and access to an extensive pipeline network that links into demand centres located both locally and further afield.

Both countries are expanding critical infrastructure to enhance their hydrogen import capabilities.

The Netherlands targets first hydrogen imports (in the form of ammonia) from 2024, with large-scale imports to follow in 2027-2028 and imports for Europe from 2030. Belgium aims to begin importing hydrogen from 2027 and be connected to Germany from 2028.

To accommodate these targets, the Netherlands and Belgium have initiated plans to build the required infrastructure (i.e. ports and pipelines).

Port Infrastructure

Figure 3: The Netherlands’ and Belgium’s proposed port infrastructure developments for hydrogen. Source: Port of Rotterdam, Port of Antwerp and Westwood analysis

Pipelines

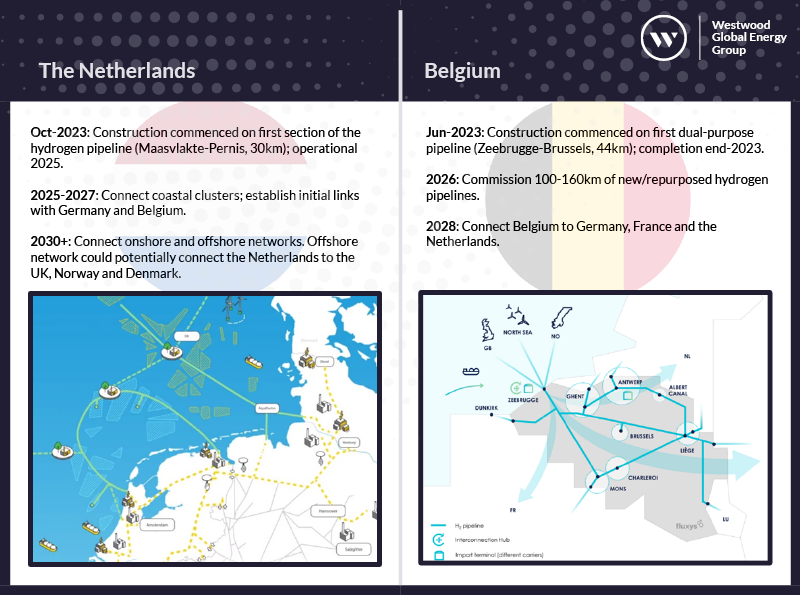

To transport hydrogen from the ports to consumers both locally and abroad, an extensive pipeline network is required. The Netherlands intends to repurpose 85% of its existing onshore 12,000km gas pipeline for hydrogen (15% will be newbuild). In Belgium, Fluxys has 4,100km of existing gas pipelines and intends to commission 100-160km of new/repurposed pipeline for hydrogen. The pipelines of both countries will initially link their domestic industrial clusters but also include plans to link into neighboring EU countries from the mid-to-late 2020s.

Figure 4: The Netherlands’ and Belgium’s proposed hydrogen pipeline networks and timelines. Source: Gasunie, Fluxys and Westwood analysis

Currently, the Netherlands and Belgium are beginning to implement their plans to prepare their respective infrastructure to receive and distribute hydrogen imports. The next question is: where should the hydrogen come from? Countries with abundant, low-cost energy – be it in the form of natural gas or renewables – can be sources of competitive hydrogen supply. Forming partnerships with these countries is fundamental to a viable import strategy.

Both countries have announced partnerships with a diverse range of potential low-cost hydrogen suppliers.

The Netherlands announced partnerships with 10 potential hydrogen supplying countries, while Belgium announced seven (highlighted on the map below). Apart from Canada, all the partner countries have announced targets for either hydrogen production or price.

Figure 5: Map of the Netherlands’ and Belgium’s announced hydrogen import partnerships. Source: Westwood analysis

It should be noted that not all countries are equal in terms of their capabilities to deliver on their stated hydrogen targets. For example, the US has strong support from the Inflation Reduction Act and $7bn of funding has been allocated to the development of seven regional hydrogen hubs, which makes achieving their 10Mtpa 2030 target more likely. In contrast, Brazil has announced an ambitious target of 350Mtpa from offshore wind and 6.9Mtpa from nuclear in its draft hydrogen plan yet has no offshore wind farms along its coastline and only one nuclear power plant in operation – thus, it is more questionable whether Brazil can achieve its proposed target. Nevertheless, the Netherlands and Belgium are taking proactive steps towards securing and developing a diverse set of trade partnerships.

The Netherlands and Belgium have funding packages to support hydrogen imports.

Despite the potential to import hydrogen from countries with relatively low-cost supply, subsidies are still required to support hydrogen production since it is more expensive than fossil-based alternatives, as is the funding to help pay for these capital-intensive developments.

The Netherlands earmarked €300m from its €35bn national Climate Fund to subsidise the cost of hydrogen, while Belgium earmarked €10m to fund port infrastructure development.

Figure 6: The Netherlands’ and Belgium’s announced funding for hydrogen imports. Source: Westwood analysis

In conclusion, the EU’s 10Mtpa hydrogen import target is ambitious and meeting this will require the capabilities and collaboration of many partner countries. The Netherlands and Belgium have an excellent opportunity to leverage their existing infrastructure, but the amount of investment and development still required is both costly and risky given the hydrogen market’s nascency. Both countries are backed by government support, detailed roadmaps, a healthy pipeline of project and infrastructure developments, financing and promising partnerships, all of which should support their ambitions to become Northwest Europe’s leading hydrogen import hubs.

Joyce Grigorey, Director – Hydrogen

[email protected]

Jun Sasamura, Senior Analyst – Hydrogen

[email protected]

David Linden, Head of Energy Transition

[email protected]

This insight and project certainty assessment is excerpted from our pending hydrogen country reports, which form part of Westwood’s new Hydrogen solution, coming soon. For more information or to speak to a specialist, please contact [email protected].

To access a PDF copy, please provide your email address below: