On the 18th of November the competitive leasing period for the INTOG offshore wind process came to a close. The goal of INTOG is unique, in that it aims both to encourage further innovation in the offshore wind sector and create an opportunity for offshore wind to decarbonise oil and gas (O&G) assets. The water depths and distances from shore of the bidding areas lend themselves best to floating wind.

The outcome of the bidding period will not be known until the end of March 2023. In the meantime, Westwood has been engaging with the industry to get a better understanding of whether the INTOG process has lived up to its expectations. The reflections in this insight stem from a broad base of developers and O&G companies – not our own opinions – and is focused on the TOG part of the leasing period: targeting oil and gas decarbonisation.

A unique leasing round

INTOG is a dual offshore wind leasing round process being run by Crown Estate Scotland for innovative projects of less than 100MW (‘IN’) and projects connected to O&G platforms to electrify them (‘TOG’). 500MW is available for IN projects, with projects limited to a maximum size of 100MW, while 5.7GW is available for TOG projects.

There is no absolute size limit for TOG projects, but there is a ‘Proportionality Principle’ to ensure that there is a sufficient focus on decarbonisation in project planning. A developer can bid for no more than five times the demand it intends to satisfy to O&G operators – testified to in the form of a non-binding Letter of Intent (LOI) and for a minimum of five years of demand. For example, if a developer receives an LOI for 100MW from an O&G operator, the maximum bid that the developer can make is 500MW.

Winning bids – chosen based on price and quality of submission – will be offered a period of exclusivity before an option agreement (seven years) and eventually a lease (50 years) is signed. Of note is the length of the lease period, which is usually 25 years in the UK.

The TOG opportunity

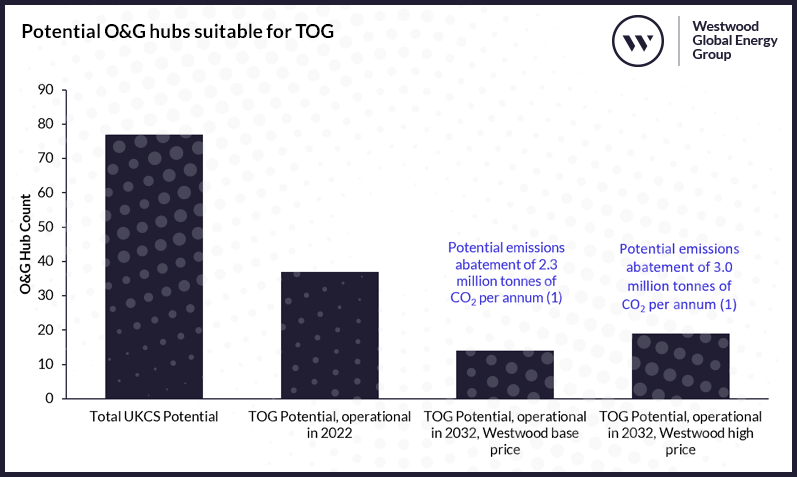

The O&G sector has, through the North Sea Transition Deal agreed in March 2021, committed to reduce operational emissions by 25% by 2027 and 50% by 2030. At least two electrification solutions are expected to be key to achieving this. There were 76 hubs in operation in 2021 that emitted a total of 10.2 million tonnes of CO₂, of which circa 70% were the result of the combustion of either natural gas or diesel for fuel. On initial inspection the opportunity of TOG appears large.

On closer inspection however, leveraging the data from Westwood’s Atlas product, the opportunity may not be all it seems. Assuming a windfarm is operational in 2027 and considering the minimum requirement of five years of demand, hubs set to cease production in that time period can be excluded. Factoring in the location of the INTOG areas available, and technical challenges in electrifying floating production facilities, the number of potential hubs is further reduced. Based on Westwood’s base case commodity price assumptions, only 14 hubs would be viable opportunities in 2032. In a higher price environment, this could increase to 19.

Factor in a maximum economic transmission distance of 100km from wind farm to O&G hub, and the power each hub will require, and it suddenly becomes apparent that the potential candidates for offshore electrification reduce significantly. The wind farm developers will also likely find themselves in competition for the same O&G hubs.

Potential O&G hubs suitable for TOG

(1) Based on 2021 reported emissions, assuming 70% can be abated due to electrification.

Source: Atlas, Westwood Analysis

Excitement mixed with concerns

INTOG has been taking place in the context of increased momentum around floating wind, and the ScotWind leasing round, where 15GW of floating wind capacity was awarded at the start of 2022. With electrification and emissions reduction, a much-debated topic amongst UK Continental Shelf (UKCS) O&G operators, floating offshore wind could provide at least part of the answer.

The unique context and opportunity presented by INTOG has attracted the attention of several offshore wind developers of old and new. However, during Westwood’s discussions with different developers and O&G companies, several concerns had been raised about the INTOG process, which have the potential to create an unexpected outcome or unintended consequences.

The below summarises a selection of the themes:

Conflicting priorities

O&G operators and wind farms have a joint interest in electrification, but divergent interests in its implementation. O&G operators will want to electrify their platforms as quickly and cheaply as possible (and have alternative options to INTOG proposals such as electrification from shore, or other nearby offshore wind farms). On the other hand, wind developers will want to develop commercially successful projects, but are dependent on the platform decarbonisation portion of the proposal. Initially relying on non-binding LOIs agreed with operators at the beginning of the INTOG process, and then balancing the different needs of electrification and successful commercialisation during negotiations in the exclusivity period.

The different priorities of the NSTA – to showcase emissions reduction and electrification progress, and Crown Estate Scotland – aiming to make the most of the seabed on offer, can complicate things further. Bids are assessed on cost, not whether they are the best decarbonisation solution.

Although the NSTA has been keen to have two electrification projects commissioned by 2027, Westwood’s base case forecast would deliver the target 50% reduction in emissions through hub closures alone. This may reduce the incentive for O&G operators to do more to tackle emissions, especially as the investment case to electrify platforms is harder to justify for platforms approaching their Cessation of Production (COP) dates. A renewed desire to maximise domestic production for UK energy security brings a further point of complexity to the debate.

Connecting issues

TOG requires a connection to O&G platforms as standard, a process that has only ever been undertaken on demonstration projects and never on a commercial basis. Additional considerations, such as cabling being the single most common point of failure for offshore wind farms, also need to be taken into account.

Wind projects are likely required to connect to the UK grid to be able to create commercially successful projects (of scale). This brings them into conflict with the ScotWind projects (and others) when competing for limited grid connection capacity available. While Crown Estate Scotland was planning on bringing projects on quickly, some developers fear this is not feasible given the challenges facing projects.

Equally O&G platforms seek a reliable source of power, requiring a connection to an alternative source of power to compensate for times when wind power from the TOG windfarm is unavailable. Without the reliable supply, the benefits associated with electrification cannot be maximised e.g., savings on UK ETS, reduced O&M, and potential increased sellable gas.

Competition

Bidders are not just competing against each other to provide the best wind farm concept (or against the O&G industry’s ‘do nothing’ option), but also against alternative platform electrification solutions (e.g., cable from shore). This introduces a further element that is hard to benchmark or compare.

Commercial viability

Wind developers have to design their projects around O&G platform electrification. However, this is going to be a relatively transient (potentially only five years) part of the demand compared to expected lifetime of the farm (and upfront investment).

Developers will also likely have to implement commercialisation strategies that integrate revenue from two distinct sources, via the ‘grid’, most likely (or hopefully) under a CfD, and the O&G operator with whom the developer has agreed an LOI.

The potential impact

Considering the complexities identified, several developers that have been targeting growth – either in the UK or specifically in floating wind – have taken a step back from participating in the TOG part of the INTOG process. Developers that have stayed in the process have had to deal with several additional considerations (and risk factors) before placing bids.

More broadly some developers have voiced a preference for a more centralised and coordinated model for O&G electrification (as has been seen in Norway, with Trollvind for example), rather than the cutthroat auction model where developers compete against each other, rather than working together to focus on deliverability.

Depending on what happens by the end of March, that could very well happen. Otherwise, the growth in floating wind and O&G decarbonisation may take more time than thought.

David Linden, Head of Energy Transition

[email protected]

Yvonne Telford, Research Director – Atlas NW Europe

[email protected]

Stuart Leitch, Senior Analyst – Emissions & New Energies

[email protected]

Peter Lloyd-Williams, Senior Commercial Analyst – Offshore Wind

[email protected]