2025 is shaping up to be an exciting year for the offshore wind sector after the twists and turns of 2024, when record-breaking successes and sharp setbacks often came in quick succession. Westwood projects that record amounts of capacity could reach FID and come online in 2025 (albeit driven by strong activity in China in the former case), while leasing volumes may rival the highs of 2024, all reflecting a sector which is undergoing transformational expansion. Here, Westwood offers five themes to track in 2025 to get beyond the headlines.

1. It’s the economy – will macro-economic conditions become more favourable for offshore wind?

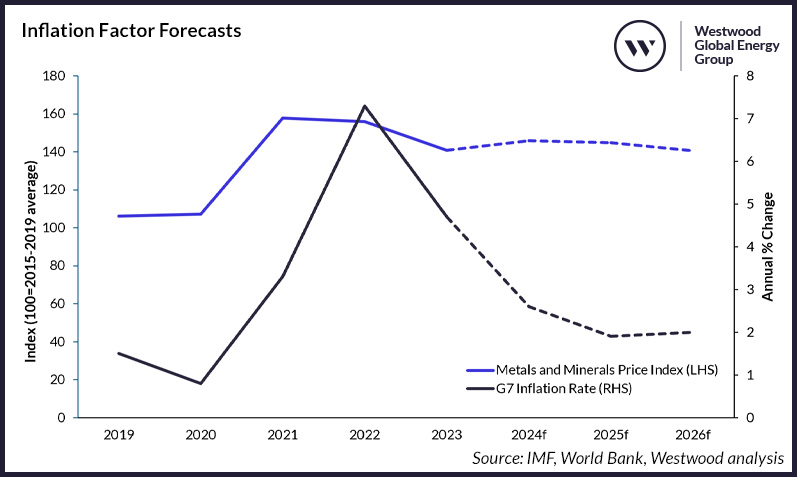

The global economy affects all sectors, and offshore wind, driven as it is by debt-based project finance and hard infrastructure investment, is particularly exposed to macro-economic shifts. Higher interest rates and elevated commodity prices in particular have been the source of much of the industry’s difficulties in recent years. There are signs however that the situation could be changing. Interest rates are moving downwards, albeit unevenly, and key commodity prices have eased back somewhat from their 2022 peak. Rates are expected to continue falling in 2025, while metal and energy prices are projected to remain fairly stable, both of which should provide some relief for the sector. Nonetheless, the potential imposition of new tariffs by the incoming Trump administration could introduce inflationary trade friction, creating a new set of challenges.

Inflation Factor Forecasts

Source: IMF, World Bank, Westwood analysis

2. More on the menu – will developers continue opting for the largest (possibly Chinese) turbine models or start to favour standardised options?

Turbine OEMs seem to be increasingly focusing on one of two marketing strategies and 2025 may begin to give us a sense of which developers are more receptive to: 1) ‘bigger is best’, where newer and larger turbine models attract developers by offering economies of scale; or 2) ‘standardisation’, where the focus is on the serial production of well-known models that developers are familiar with. The ‘bigger is best’ philosophy has been the default approach of both OEMs and developers for some years now but has also played a role in the profitability issues that some manufacturers now face. In this view, volume production of highly optimised standardised units is a way for OEMs to meet soaring turbine demand while retaining profitability.

It will be fascinating to see whether developers, under pressure to meet capacity targets, prefer to use familiar models (say 15 MW) or adopt novel units (say 20 MW) in order to install (say 25%) fewer turbines overall. However, regulators are increasingly requiring developers to demonstrate, as part of their applications for lease and subsidy, that the technology their business plans depend on will actually be available when needed. Theoretically, this sort of provision should disadvantage developers intending to use units that still need to be developed, but what impact it has will depend on each regulator’s ultimately speculative view of the technology curve.

In any case, a further complication is that many of the largest turbine models being developed are from Chinese manufacturers, whose approach to financing, warranties and O&M is largely untested in the European offshore market. Given past precedent, it seems likely that the largest available turbines will remain most attractive to developers, so long as they have confidence in the security of their supply and the necessary installation vessels and facilities. There are, after all, perhaps five to 10 WTIVs in the fleet or on order capable of installing ~20 MW turbines.[1]

Turbine Model Evolution by Turbine OEM

Source: Westwood WindLogix

3. Float forwards – will the floating offshore wind supply chain start to take shape?

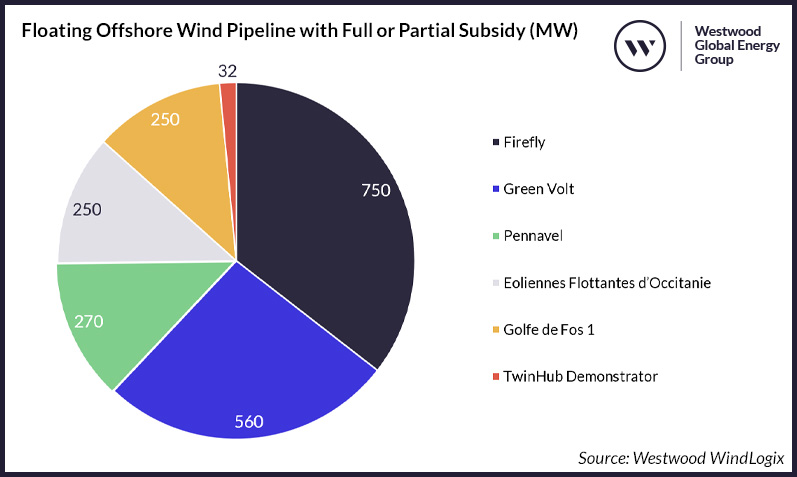

2024 was a relatively positive year for floating wind, with several large projects across France, the UK and South Korea securing the subsidies which should enable them to reach FID in due course. With more significant floating tenders set to conclude in 2025 (e.g. Celtic Sea in the UK, Utsira Nord in Norway) and more details potentially emerging about 2024’s winners, could 2025 be the year that the floating supply chain starts to take shape? While an upsurge in optimism may be premature, we should start to get a greater sense of what the industry may look like in future (assuming the supply chain is ready to start offering commercial volumes). As recent years have amply demonstrated, the proof of the project is in putting steel in the water. Even fully consented and funded projects can be derailed by changing economic and political conditions.

Floating Offshore Wind Pipeline with Full or Partial Subsidy (MW)

Source: Westwood WindLogix

4. Walking the walk – will government support finally measure up to lofty ambitions?

Many governments have big plans for offshore wind, but the financial and policy support they make available has not always been the equal of this ambition. This has led to some high-profile setbacks in recent years, with offshore wind offerings in the UK, Denmark, Estonia, Lithuania, the US and Japan all failing to generate the expected level of interest (and in some cases, any interest at all). The better news is that, excluding the highly unusual situation in the US, governments have generally responded to these setbacks with supportive policy reforms. While developers are unlikely to get everything they want from government in the coming year, recent reforms may constitute a sufficiently critical mass of change for regulation to become less of an impediment in 2025. Moreover, a number of lease and subsidy auctions are likely to conclude in new markets in the coming year (e.g. India, the Philippines), which should give us a sense of how successful governments in these countries have been at creating regulatory regimes that stimulate bidder interest.

5. Invest at leisure, divest in haste – what next for oil and gas companies in offshore wind?

Oil and gas operators entered the offshore wind sector in the early 2020s, to much fanfare and at great expense, before retreating through 2024 in the face of unimpressive returns and discontented investors. The E&P players alone were responsible for 4.3 GW of net project divestments in the year. So far, the general strategy among E&P companies seems to have been one of ‘hive off and hibernate’, with operators selling off their holdings (or moving them into JVs) and aggressively limiting short-term capital spend on offshore wind (or sharing it with JV partners). The most significant role for oil and gas companies in offshore wind in 2025, then, may be one of conspicuous absence. This would be a partial reset for the sector, returning it to something like a pre-2020 state, where established renewables developers represented the industry’s largest players.

So, there is much to think about heading into 2025, from macro-economic trends to supply chain strategies and government action. Once again, the coming year promises to be a fascinating one.

Peter Lloyd-Williams, Senior Analyst – Offshore Wind

[email protected]

[1] Assuming 20 MW turbines feature a hub height of ~165m