Energy Transition Now - Episode 28 with Johan Sandberg

For a technology that is essentially still in a pre-commercial phase, the expectation is high for floating wind to be the future of the offshore wind industry. But the technology landscape that is going to help floating scale is far from settled. With vertical axis wind turbines having been around for just as long as horizontal axis ones, floating also presents an opportunity for vertical turbines to play a bigger part. To discuss how the floating offshore wind sector has evolved, and the role that vertical axis turbines can have in the growth of this market, David spoke with Johan Sandberg, CEO of SeaTwirl.

About Johan

Johan Sandberg has worked with offshore wind power since 2008 and has been especially focused on floating wind turbine technology. He spent almost 12 years in DNV where he – among other things – had global responsibility for offshore renewables advisory services, responsibility for developing the world’s first design standard for floating wind turbines, and the world’s only guideline for integrating offshore wind with offshore oil & gas assets. In 2019 Johan joined the Norwegian industry conglomerate Aker and as Head of Business Development in Aker Offshore Wind, and since March 2023 he is the CEO of Swedish floating wind technology developer SeaTwirl.

David Linden [00:00:00] Hello, everyone. I’m your host, David Linden, the head of energy transition for the Westwood Global Energy Group. And you’re listening to Energy Transition Now, and specifically the offshore wind mini-series. If there’s ever a conversation about the future of the offshore wind industry, you cannot get away from talking about floating wind, a technology that’s essentially just coming out of a pre-commercial phase. Ready to scale. Or so many of the industry are certainly hoping so. Either way, the exact technology that will be part of that scaling is still very much up for grabs. So to talk about floating wind and specifically floating vertical axis wind turbines, I’m super pleased to have Johan Sandberg, the CEO of SeaTwirl and I quote “industry veteran” on with me today. Hello, Johan. Welcome to the podcast.

Johan Sandberg [00:01:01] Hello, David. Thank you very much for inviting me here.

David Linden [00:01:05] No problems at all. And do you feel like a veteran or was that an unfair comment?

Johan Sandberg [00:01:13] Well, I can’t really say that I do, but considering that I’ve pretty much spent my entire career in the floating offshore wind industry, I suppose I’m one of the few people who were actually there in 2008, 2009 when the first full-scale turbines were installed. So perhaps you’re right.

David Linden [00:01:33] In relative terms you’re a veteran. I like that. But I guess that gives you a sense of in one way how young this industry is, but also there is some real history there. So maybe let’s start with that. You how did you get involved in the floating wind industry?

Johan Sandberg [00:01:51] Well, I mean, first of all, you know, when you graduate from uni, you have or at least I didn’t have any idea about where I was going. I wasn’t sort of sure which industry I would end up in or any of that. But, you know, I wrote my master’s thesis at university about modularisation and we looked at mobile phones, cars, trucks, trains and aeroplanes, so I could sort of end up in any of those industries from small to big. But I somehow ended up in the UK. I was recruited to a management trainee program and moved to London and I ended up in risk management. And risk management is also very wide and it could almost be applied to anything but there was a terror attack in London in 2005, as you may remember.

David Linden [00:02:38] And so, yes, yes.

Johan Sandberg [00:02:41] It drew a whole lot of attention to business continuity for businesses. So, yeah, so I ended up in that space looking at how can the industry or sorry, companies rather continue their operation under some pretty special circumstances. I moved to London, worked in risk management and business continuity and I sort of found out that there are four existential threats to mankind, basically. One of them was the pandemic, which I was working quite much with actually, for a couple of years. Another one was nuclear war. The third one was an asteroid hitting the earth, and the fourth one was actually climate change. So those are sort of the existential threats to mankind. And it was interesting to sort of work with that in mind anyway. Yeah. In your daily business. But when I moved back to Scandinavia, I actually came to Norway and started with DNV back in 2008. And DNV works with risk management. So it was a natural place to begin working with. Pretty much straight away I came across offshore wind and in 2008 it was sort of early days for offshore wind and it was all bottom fixed. But I came to Germany and I saw the turbines being installed out at Alpha Ventus, and I was just blown away by the size and just the sort of impressive sight of these huge turbines. They were five megawatt turbines. It’s a very, very big at the time. But still, you know, when you see them and when you consider the risks of installing them offshore and operating them offshore, I just thought this is a really exciting industry. This is something for me. So I just you know, I just fell in love with that industry straight away. And in DNV, it was still also pretty early days. It wasn’t a huge amount of work in that space at the time. So I kind of took that ball and ran with it. And in the advisory services space where I was working, I eventually became responsible for a team focusing only on floating and bottom fixed offshore wind at the time. Okay. And then just a year later, in September 2009, Statoil Hydro installed the world’s first full scale floating wind turbine here in Norway. So that was the HyWind, 2.3 megawatt turbine. And, you know, since then, it’s also been quite clear to me that the floating wind space is actually quite different from bottom fixed. It is a different type of challenge and complexity when you have a floating structure compared to a bottom fixed structure. So we could see that this industry had huge potential. We wanted to gather the industry to accelerate its development. So we started a joint industry project as DNV always does when they want to to to progress industries forward. And they invited, you know, interesting companies who were interested in this into the GIP, basically. And that resulted in a design standard for floating offshore wind turbines the world’s first actually. So that was launched in 2013. And obviously, you know, we made a big thing about it, and I think it helped the industry forward when that came out. So during those years, I was working together with the companies that were very active at the time. So we had obviously Statoil, as they were called. Nowadays it’s Equinor, but it was very active and it was Principal Power with the semi submersible design they had. It was Glosten Associates who had their Pelastar TLP platform and I think slightly after also ED Oil came with a barge design as well so. So those years were just very exciting. It was pretty small community. We met around the world, sometimes in the US, sometimes in Japan, sometimes in Europe. And it was a little bit of a family feeling, I think, in those days. And I loved it. It was it was amazing. And we could really see this bright future for floating wind. And then in 2011, I started an MBA in energy management. It was with Nanyang in Singapore, IFP in Paris, and Oslo BI here in Norway. And right in the very beginning, the Fukushima disaster in Japan happened. So literally in front of our eyes, we could really see how the entire industry, sorry energy industry or energy system in Japan had to shut down is right when we were in this Start-Up of a big sort of MBA course. And right then I decided that I want to write my master’s thesis for this MBA about floating offshore wind in Japan. So after that, I spent a couple of years almost just going back and forth to Japan, not just writing the thesis, but also to speak to industry and see if we could sort of help Japan replace some of its energy production with floating wind. We could also see and I think this was very interesting, we could also see that in the northwest of Japan. Sorry northeast, on the Sendai coastline, the almost the entire fishing fleet had been destroyed by the tsunami. So there was also a huge need to rebuild the fishing fleet and vessels. And we were thinking about if we could design a new type of vessels that could be multipurpose for both floating offshore wind and fishing or aquaculture. So there was also a lot of focus on, you know, collaboration between industries and multipurpose vessels there. And that’s a very interesting actually. Yeah, those were the early days anyway. And. Yeah. I still find it just as exciting as I did then.

David Linden [00:08:42] I can imagine. I mean, look, that’s only like a decade ago, right? All of this was all slightly over a decade, but. But even then, you know, the industry was so young. If you put it in those words, which is great. And now what we have with a couple of hundred megawatts, a little bit more in in the water, plus a series of pilots on top of that maybe as well. So the industry isn’t, quite there yet because of various factors. And we could spend, I think, the entire podcast talking about why isn’t quite there yet. But part of I guess this is a use case, right? And why would you build Floating wind? And it’s interesting like, you know, you talked about Japan. I mean, Japan is still the if you were in Japan last week said, well, the recording last week, well, a series of events on in Japan and the wind expo they had and other conferences that industry still struggling to get off its feet and develop. But right when you started off and were talking about this and there was quite a bit of marketing done around something called the Win Win project that you talked about. Right. And that vision, you started to sort of indicate that around, okay, there are different industries that can benefit from this. And then there’s that vision of maybe the integrated ocean economy, if you put it in those words. But actually initially and you can tell me if I’m wrong here, from what I’ve interpreted it was about floating wind powering or certainly supporting the production of oil and gas platforms. At its simplest level, because this can this is a big topic in itself. But is that still the case? Are we still talking about look, you need to be looking at specific use cases like oil and gas platforms for the industry. So, you know, even though it was almost ten years ago, you first came up with this. If this is still the case and then the vision is the ocean economy as such, are we still at that stage? Are we still saying oil and gas platform electrification’s the starting point here, guys, or have we moved on?

Johan Sandberg [00:10:57] No, I think the answer is no. We have moved on. And I would actually say, unfortunately, because what I was hoping for back then and just to explain the background there, the thing is, DNV was celebrating its 150th anniversary in 2014. And before that anniversary, they wanted to create visions for the different industries that they were active in. So there was a vision created for the maritime industry, for the oil and gas industry, and for the renewable industry. And I had responsibility for that renewable industry vision and obviously floating offshore wind. So we had a great team working full time for more than a year, just trying to forecast what the industry could look like if all the right sort of elements fell in place and that vision stretched all the way up to 2050 and it resulted in a huge report in a in a bunch of that sort of presentation and other materials. But most of all, in a video that’s still on YouTube today. And if you’re interested, it’s fantastic. I think I’m still quite proud of it, to be honest. Just type in DNVGL offshore wind and it pops up there and the background was a little bit about this master thesis I wrote in Japan. It has a sort of imaginary place that sounds like a Japanese place. It’s called Naigashima Continental Shelf, and Naigashima isn’t a place that actually exists, but it sounds Japanese, a bit like Fukushima almost. But if you take the three words Naigashima, it’s ‘new’, ‘wind, ‘island’… ‘nai’, ‘gas’ and ‘shima’. So we thought, can offshore wind become for Japan? What say oil and gas became from Norway? You know, can it be sort of almost become the backbone of their economy in a way? And that’s why this hypothetical place or project called Naigashima Continental Shelf came about. And obviously that was the 2050 place. You know, when it’s all built out, it’s all, you know, very low cost of energy and all that. But we realised that in order to get there you need to have a catalyst market or some kind of catalyst, you know, process to get there. And that we thought was oil and gas, because we could really see the huge energy demand on the oil and gas platforms, the huge emissions that comes from oil and gas, and the fact that quite a lot of this could actually be replaced by wind. And if you look at the power consumption in the offshore oil and gas industry, a very large part of it. In fact, I think the largest part of it is for water injection, for enhanced oil recovery or for just, you know, pressurising your reservoirs. And that is one of the processes that isn’t as critical as all the other processes on the platform. You can actually, you know, increase and decrease quite a bit with water injection. So we thought this is a perfect match. You can really do a lot of water injection with the wind, with the wind turbines, and that’s where this Win Win project came about. So a lot of people think it’s wind, wind or win, wind, but we just call it Win Win because that’s what it really is. It’s a win for the oil and gas industry, and it’s a win for the wind industry as an accelerator of floating wind turbine technology, basically. So we were really hoping that, you know, by now we would have quite a few of these floating offshore wind installations to support the oil and gas industry and thereby qualifying these new technologies.

David Linden [00:14:35] Right. But that was the scaling opportunity. That’s right? Okay.

Johan Sandberg [00:14:40] And I think in the video, it says that by 2025, the oil and gas industry is using floating wind turbines. And, you know, we’re pretty much there because Equnior is now building HyWind, something doing exactly that. But unfortunately, it’s the only one. So far. We’re having some company as well. So hopefully it’s going to be more.

David Linden [00:14:59] Yeah. I mean, there was there was a non floating window and I guess it was Beatrice in the U.K., I believe was there as well. And obviously, you’ve got the INTOG round in the U.K. as well where there is an expectation. But I think overall, that’s I mean, let’s see what the results say. By the time this comes out, maybe the results are out, but I suspect it takes a little bit longer. But, you know, it’s been at all underwhelming, I guess, and other concepts like TrollVind are going back to shore before they electrify a platform. So the world has moved on. But also in general, technology has moved on and the discussion around what it can do obviously has grown significantly, right, whether it’s large scale electrification of electricity. So to help decarbonise sectors or maybe even for green hydrogen production or whatever it might be. Right? Some of these bigger concepts being discussed. But you know, there are days of conferences to talk about those sorts of things. I think the one thing I’d like to maybe move our conversation on to now, Johan, is, you know, floating wind has been around now, let’s say, a couple of decades. Let’s just say as a concept then now there’s a few commercial projects in the water. And the discussion typically that happens is people say, look, there are almost a hundred or plus 100 plus, depending on how you count it, different foundation designs that are out there, you know, which ones are going to win, why, you know, what do we need to do to maximise those, etc.. And typically, typically not all of them, but they’re reusing I guess existing horizontal axis wind turbines as part of that. Right? So really a conversation around the floater itself, or the floating design itself. So. You obviously are the CEO of a business now that’s looking at vertical axis wind turbines. That’s less well known, I guess, relative to the conversation that’s been happening in this industry. So, it would be good to hear from you, maybe in your own words. Essentially, what does a what does a vertical wind turbine actually add to this mix? Aren’t there like a whole series of other things to sort out first using existing technologies? What, why vertical, I guess?

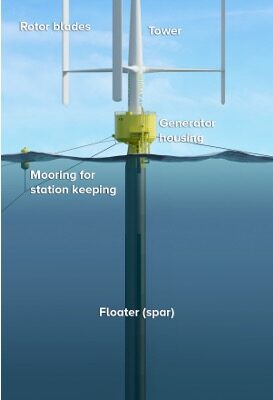

Johan Sandberg [00:17:22] Yeah, But I mean, it’s a great question and no surprise that you’re asking. Of course. But I mean, I’ve spent 15 years working with the conventional wind turbines, put on a floater. And of course, I think there’s a tremendous future for that. And there is absolutely no doubt about it that this is not something that’s going to come in and, you know, entirely disrupt the industry and suddenly everybody’s going to realise that it’s all going to be vertical turbines. I don’t think that’s the case at all. But like you say, vertical axis wind turbines have been around for just as long as the horizontal axis ones. And, you know, I think the first one was recorded 3000 years ago with something in Mesopotamia, you know, a tiny little turbine. But, you know, they have hundreds of years in operation. But, both turbines, you know, the windmills in, you know, around the world as well. Yeah. So I think it was really in the seventies and eighties where it was actually a pretty tight race between horizontal and vertical axis wind turbines. And in California, you still see some vertical turbines today. So the pros and cons of a vertical axis, wind turbines are well known and well documented. So there isn’t really a whole lot new about that. But what I think is interesting is that obviously the horizontal axis wind turbine won the race to commercialisation, you know, a long time ago for a number of reasons, but in a floating context, things are rather different and, I think it’s just very interesting to explore the opportunity of the vertical axis wind turbine in that context. And there are a couple of things that I think is worthwhile highlighting here. So one of the reasons that the vertical turbines could really grow big on land or on bottom for that matter, is the fact that just the load on the bearings that will hold the rotor is just so big that it becomes extremely expensive and difficult to have bearings to hold that load. So the very idea about SeaTwirl where I’m working today is that in the floating context, you’re actually able to let the shaft go straight through the generator and therefore your substructure, which in our case is the spar, will also have to rotate under the water. And if you if you see a little video of it or a picture, you it would make more sense. But if you think about it, it’s really just a doughnut looking generator house that sits on the surface of the water floating. So it has a sort of zero real weight because it’s held by its buoyancy. And that doughnut generator house is moored to the seabed. You then have the vertical axis wind turbine on top of it and you have a steel pipe essentially, or a pipe which is a monopole underneath the water, and they’re all completely integrated and connected and therefore it rotates. The whole shaft is rotating.

David Linden [00:20:25] The whole shaft is rotating. Okay, So all right, if we just pair it back one second, those are folks who maybe don’t focus as much on all the different concepts. Your horizontal turbine is essentially like your classic windmill, but modern in its look and feel. And your vertical is almost that. As you say, that turbine turned on its side as such and spinning around in front of you. And that’s it’s like a helicopter. It’s really simple for people who have no idea about this industry. And what you’re saying on top of that is, is that the whole shaft in this instance and including under the water as such, it is moving in its entirety in the SeaTwirl design, which is kind of almost a third iteration, if you put it in that sense of the design. Am I saying that in its simplest form correctly?

Johan Sandberg [00:21:24] Yeah, I think we put the picture up as well for people who are interested who could actually just go in and look at that. So it’s going to make more sense when you actually see it in front of you. But you’re right. That’s basically it. So the big difference here is that for a normal wind turbine, you have your generator at the very top of the tower and then the rotor is obviously attached to that generator. And the difference here is that you have put and you placed your generator and all that weight at the very bottom of the tower on the surface of the water, basically. So a key aspect here is just access to all that heavy equipment that is in the generator house. And the other thing is the fact that you have taken the point of gravity from the top of the tower to the very bottom of it. So. So for that reason, we think that the substructure can become significantly lighter just due to the fact that you have placed that very, very heavy piece of equipment right on the on the surface. And hopefully also the substructure can be a very simple piece of kit to produce and to industrialise. So we already today see a huge industrialisation of the monopiles that are used for bottom fixed offshore wind. And the ambition here is to use exactly that same supply chain. And, you know, I think the industry is pretty focussed on looking at how much steel we’re using per installed megawatt per produced megawatt hour. And I think it’s going to be an even more importantant one going forward because we will have to come with a very strong sustainability story. We will have to eventually use green steel for our products. You know, we’ll have to use recyclable material and all that as well. So the steel weight per megawatt is going to be an important factor to develop for the future. Yeah. And, you know, one of the strongest sort of benefits of this, I think, anyway, is the fact that you have an integrated structure. We have eliminated the interface between a turbine supplier and a substructure supplier and all the complexity that comes with that. Because you have a control system controlling the turbine, the forces are going to have to be, you know, going into the substructure. And that is a very difficult interface and it requires a lot of collaboration between different organisations and so on. And with a single structure integrated right from the very beginning, we have eliminated that risk altogether and we can basically sell a structure for a unit costs instead of, you know, a couple of components like that. It’s a unit cost where the turbine and the substructure is all integrated into one. Yeah, just another thing about vertical turbine, and this is not just for SeaTwirl but for any vertical turbine, it’s basically that the blade has the exact same profile over its entire length. So that also enables a different type of mass production or industrialised production of the Blade. We were definitely looking into that and we are right now actually producing the blades for the prototype that we’re going to build here in Norway next year. The S2 if all goes to plan and, and it’s just a fantastic sight where you see a blade that has the exact same shape all along. And that also opens up for sort of innovations in production as well. So that’s an interesting one, I think. I was also quite intrigued by the team when I met them, and I think there’s something about the culture in the group that you, sometimes you meet a group and you feel it hardly matters what they’re doing, but it feels like they’re going to achieve something in there. There is something about that sort of glimpse in their eyes when you see really dedicated people, and I just love that. And I was attracted to that. And I saw an interview with Elon Musk once where he basically said that it’s not money that is the constraint here. The constraint is a small, dedicated team who’s willing to take the risk and who wants to change, you know, the industry. That is the constraint here, because obviously he was challenged about, you know, the very little resources he had back in the days compared to the big automotive companies. And again, we are very humble. We are not thinking that this is going to, you know, turn it all over. But I think we think that there is an opportunity here that is really exciting. And another thing is that just the fact that the turbines are now growing so big, the conventional turbines are now growing so big, 16, 18, 20 megawatt turbines requires such big vessels that you need big fields to justify hiring in those vessels. Yeah. And all these opportunities that we talked about for smaller projects, not necessarily, you know, very small turbines, but a fewer turbines, it’s going to be very difficult to justify hiring in huge vessels with a crane capacity to do the heavy maintenance on the very top of the tower if you only have a handful of turbines. Even if you’re electrifying a large oil platform, you would still only need a few turbines. And that market is going to struggle when you need that huge economy of scale to work with the big turbines. So I think that this catalyst market that we talked about before, that’s still there and that’s something we want to sort of explore as well. And in fact, there is need for small turbines, you know, like the fish farms, they need very small turbines. So it could be a ladder for us here to start with the you know, obviously the prototype we’re developing right now which is only one megawatt. But then, you know, to be a ladder of development all the way up to the big ones.

David Linden [00:27:12] Okay. Well, let’s. Talk about scaling in just just a minute then. But, you know, you what’s so what I hear partly from what you’re saying there, Johan, is it’s around, it’s not about completely disrupting industry. It’s about providing in addition to what’s going on right now. Right. And there are there are certain factors about this design in particular that just offer different benefits to the industry and to the potential user of the electricity. So when you’re designing it, when you’re using it, there’s a sustainability angle around, as you say, the and also cost my assumption angle as well for the steel weight per megawatt discussion, the whole idea of mass production using existing or mostly existing supply chains, which I guess also plays to your local content piece. So if you’ve got that, you can actually reinforce that rather than having to reinvent the supply chain or go and produce these things elsewhere.

Johan Sandberg [00:28:08] And then I’ll just sort of collaborate a little bit on that.

David Linden [00:28:11] Please do.

Johan Sandberg [00:28:12] Yeah, this is this is the unique thing about having your generator house down by the surface where it’s carried by its own buoyancy. It basically means that you’re not as restricted to sort of minimise the weight of that generator house. You can actually sort of accommodate a philosophy around the modularised approach for the equipment in the generator house and replacing that equipment. So for instance, if you would, if you think about it as a obviously the ring is also the shaft is rotating inside this ring generator house or doughnut shaped generator. Yes, you can have a number of smaller generators in there for easy maintenance, easy replacement, but also the industrialisation. You can have much more standardised components going into that generator house because it is so accessible, probably larger because it’s not as restricted by weights and you have a bigger degree of freedom in there. Having said that, we also have obviously the challenge of a spar design for the substructure that requires a certain water depth. So we are probably not going to be able to build in the shallow end of the floating wind market. So we probably need 100 metres water depth or more so. So again, bottom fixed is all going to be conventional. Very large part of the floating offshore wind space is also going to be conventional turbines, but it’s going to be such a big market that I think there is definitely opportunity for where our technology and other technologies too. And eventually it’s going to be obviously converting into to a few, I think the potential here is amazing. And I’ve seen enough of this industry to realise how important it is to do the industrialisation part right. It’s easy to think that you need to have an optimised design for, for weight or for, you know, performance or whatever, or even for the supply chain in the local country. But unless you really get the industrialisation and mass production right, we’re going to struggle with that. See, we so modularisation, like I wrote my master’s thesis about 20 years ago, that’s going to be a key factor here. Also for the same submersibles and all of those as well.

David Linden [00:30:32] Yes, it’s an argument a lot of people make about the industry as a whole, but someone else described. The industry. What needs to happen actually is serialisation rather than industrialisation. And I don’t know if whether you agree with this, but the idea that you need to be doing is you can’t have just one, patly what you’re saying, you can’t just have one design, you can’t just have one standard. We need 100% produce just this. What you’re saying is, is I need to produce a lot of this. Then there’s a different use case. I need to produce a lot of that. And then it’s a different use case. Each produce a lot of this, and that might be about the size of the turbine. It might be the type of substructure you use or the floating design you might use, whatever it might be, but you’re not just going to find everyone is going to use a concrete design, whatever it might be, everyone’s vertical suddenly or whatever it is. But you need a whole series of, I guess, relatively industrialised but essentially serialised designs that are going to go out and someone use the car industry to explain to me, I’m not sure about the car industry side of things, that doesn’t quite work, but the whole serialisation side of things is that kind of part. What they hear from you here is, is that fair? Because there’s a there’s kind of room for everyone, but you need a few specifics that do need to grow design and then the industry moves on in the cable. Then you need the next design to come in and grow and develop. Is that a fair way of looking at it, do you think?

Johan Sandberg [00:32:01] Yeah, I suppose so. I think for floating wind in particular, if, if you’re going to have support schemes in place, those governments are going to expect a huge amount of local value creation. So you will have a lot of local content expectations in your projects. We saw that in Scotwind, We’ll see it in Norway and we’ll see it elsewhere. And therefore the local supply chain, either the technology will have to adapt to the existing local supply chain or the local supply chain will have to be, you know, investing a lot of money in order to actually build these structures. And we’ll see both. I think obviously it’s like Korea, you have a whole lot of maritime construction, sort of shipbuilding there. So those yards are more used to flat panels and so on. So you’ll have more of those type of designs there. Perhaps the same in Japan, but you know, for new yards or upgraded yards, they’re going to be more adapted to the sort of optimal design of all of the structures. I think we’ll see a whole lot of concrete. Concrete is easier to do more locally, different sort of profile on your labour force going into a concrete type of production line. But we’ll see a whole lot of different designs. But I think we will also see a lot of competition for those big yards and those facilities. Oil and gas is still there. They’re going to require huge amounts of capacity in those yards. We see military, you know, taking a lot of space in those yards, CCS projects and, you know, other big mega projects as well. So in order to open up for the smaller yards, the smaller players, we also need to think creatively around how to design to utilise those smaller players in the supply chain as well.

David Linden [00:33:51] Okay, Fascinating. No, it’s very interesting. And your point also around the content expectations. I think the EU just reinforced that with its qualitative bidding criteria they expect to see in auctions. That’s just in especially in the EU, I guess, but also elsewhere in the world. That’s just being reinforced further and further. So anything that you can do, whether it’s about helping with the biodiversity, right, but also the local content and labour side of things is going to be a major plus to what you do and what you offer to the industry. So fascinating. Okay. So, in terms of SeaTwirl itself then, so you sort of started to briefly mention just quickly around what is know what you’re doing next in terms of the prototype, what you’re hoping to do, etc.. Can you maybe just briefly walk us through what is your what is your kind of how do you go from Start-Up to scaling kind of concept? What what’s the plan if you if you’ve got it appreciate you’ve been in the job less than a month. So okay, by the time this comes out, you’ll be over for a month. But at this point in time, what’s the kind of basic plan and of appreciating you obviously going to do some more work to flesh that out?

Johan Sandberg [00:35:01] But one thing I haven’t actually mentioned yet, but is definitely worth saying is that SeaTwirl installed its first prototype in the water back in 2015. It’s been out there now for almost, well, at least seven years, more than seven years out there spending on the west coast of Sweden at the place called Lysekil. And it’s a very, very small turbine, but it has still validated a lot of the principles and the models that has been used for the development. And now that we see a demand for pretty small turbines, there aren’t really that many who has actually been in the water. So in a way, you can say that we have a qualified turbine for the very, very small turbine market, if you say so, that that is actually a great opportunity, which I think is very interesting. But then obviously the next step now is to build, S2 to prototype. We got the consent in place only about a month ago, I think a little bit more than a month ago now in Norway. So we can hopefully press ahead with that pretty quickly and install that, you know, as soon as possible. That’s going to be a megawatt turbine and therefore sort of qualified for that size. And then as we sort of go forward, we just aim to be a player in the big market with a big turbine sort of and the big projects are built. And, you know, like I said before, the pros and cons for vertical turbines are well known and well documented, but only for a certain size of rather small size. When you go to that very large scale and size, there are also unknown pros and cons of all the vertical axis wind turbines, and that’s what we’re going to try to explore. Now, you know, in the real big scale, you know, when I was sort of considering this job contemplating it, I asked for advice from the people who I really trust in this industry who were also around in the seventies and eighties when, you know, when these turbines were sort of developed onshore and they said or I got this recommendation to speak to Mike Anderson, who is a famous person in the wind industry. He founded RES and he spent a lot of time, many years developing a vertical axis, wind turbine, wind turbines. And I think at some point he had said the VAWT could basically stand for Virtually A Waste of Time. And basically what they said was, was if you can convince Mike, then I don’t think there is anyone who would be able to sort of argue against you. So what we have been able to do now is to attract Mike into the board of SeaTwirl. So he’s now on the board of SeaTwirl. We’re just about to start up working together here. And obviously he’s he’s also new in this. But just the fact that he’s going to be working together with us gives me great confidence that we will really be able to not learn lessons that has been learned before. We’re only going to spend our resources learning new lessons and really explore turn every stone on the vertical potential of vertical axis wind turbine wind turbines in the floating market. So I’m incredibly excited to have him on board and to work with him. And we will also be working with other, you know, prominent figures from the industry. We will have an advisory board to work with. So yeah, very exciting time times ahead for us.

David Linden [00:38:22] Great, great. And look, I appreciate you’ve just been a little time in your role in this. Still a lot to do, but it sounds like very exciting things to see coming from your side. Floating wind market. It’s kind of a fork in its road right, today. There’s a couple of different ways it can go. There a lot of discussion on it. I can’t even count how many conferences there are on floating wind these days write, let alone wind in itself. Everyone’s talking about it. Everyone’s trying to scale things. It’s exciting to see businesses like yours, you know, as you say, have actually been around for a little bit now, taking it really seriously and getting right to how do we really scale this thing. Is there a risk that this industry stays as a niche or niche if you’re American, right? A such that the the, you know. Too much focus, especially in today’s world, is on cost reduction and scaling. And look, if you support us enough, don’t worry, we’ll get there. Right. Like I think the latest CFD numbers just came out for the next round in the UK, and I think was it floating still at 116 I think. Maybe even the higher than that. But yes, 116, relative to the fixed one of around what is it, 44 I think. I can’t remember now but. So there is still a massive gap, right. To have, and okay, that’s the UK which is quite specific maybe. But that gives you very clear indicated that there’s still a long way to go. Is the industry at risk of being too little, too late and or saying too little too late because it’s small, but there are so many other things to push? Why push floating wind? Is it just a niche thing that is going to happen? Right. And it’s a challenging question, but we might as well end on a challenging question, Johan.

Johan Sandberg [00:40:17] I mean, if you look at where the bottom fixed industry was some ten years ago, we were also there. We were also had more than €100 or pounds per megawatt hour. Yeah. And it was also a huge concern that will we actually be able to break the €100 mark, you know, in the next two years or so or what else, you know, what would happen if we don’t? Would support disappear or what would happen? But the industry managed to do that. And also very quickly and I think it was due to huge investments in the infrastructure. So all the vessels that we see now building these, bottom fixed projects, they were basically sort of built or invested in back then and that brought down the cost of energy for offshore wind. Along with the investments in the yards, the mass production of monopiles, you know, the fantastic development of the turbines and all that. So the industry managed to do that through these huge investments. So, you know, if you need billions to into the yards to produce floating wind turbines, I think that can happen. And I think that can reduce the cost of energy for floating as well. So I’m optimistic about that. What concerns me, though, is just the fact that there are so huge targets now for the whole offshore wind industry, but on fixed as well, that the sheer volume of turbine demand is gonna also be, you know, a constraint, a bottleneck. And if there is just so much demand for bottom fixed projects, would it be natural to sort of focus on the floating as well. Would you have a risk premium or just additional costs from the OEMs to floating? And would that then make it a bit less attractive? How could that play out? Just the fact that we have such a bottleneck in the OEM turbine space, this is a concern, I think. And then, you know, like you said, you have this the zero, or now the European equivalent of the IRA, you know, Zero Emission Act or whatever, that’s going to sort of try to keep production within Europe. So, you know, Chinese turbines, are they going to be able to cover that sort of gap? I’m not so sure. But I think the industry’s is still in a little bit of a risk there because we need to see the cost compression in floating offshore wind as well. And I think the politicians need to see that coming in the next, say, 8 to 10 years. Otherwise we could risk, you know, support being pulled back. So we need to demonstrate that we can achieve this cost compression for sure.

David Linden [00:42:59] Absolutely. Yeah. There are still, you know, the key levers in place which is around decarbonisation. It is around jobs and industrialisation actually as well. Right. Preserving those industries and supporting and growing those industries. So there’s still a lot of very positive political drivers for the industry for sure. It’s just a question, I guess maybe where do those industries suit best? And, you know, always a risk that some things are pulled back because some of these they’re reliant on government decisions. But to be frank with you, overall, the positivity around the industry, I would struggle to see if it doesn’t grow into something, you know, significant over the next decade or so.

Johan Sandberg [00:43:42] And I mean, the sheer momentum we see right now, in fact, in so many markets I think will definitely get to push through and get there. So I’m very optimistic.

David Linden [00:43:53] Absolutely. Absolutely. All right. Johan, I’m afraid we have got to end it there. But thank you so much for your time. You know, so soon after you’ve joined SeaTwirl as well. I know you’re a busy man. I appreciate it and appreciate you sharing all your good thoughts with us.

Johan Sandberg [00:44:10] Thank you very much, David. Lovely to be here.

David Linden [00:44:13] Thank you. No problem at all. And everyone who’s listening, we’ll also post some links to videos and images as well. Certainly of the SeaTwirl design and also maybe to that DNV video as well. So everyone kind of just gets to visualise some of this, if you’re not in the industry in particular, you may struggle to understand some of what we’ve described, but hopefully that’ll help visualise things for you. And thanks for listening. Hope you enjoyed it. Do subscribe and talk to you next time.

Copyright and Reproduction

This website contains material which is owned by or licensed to Westwood Global Energy Group. This material includes, but is not limited to, the design, layout, look, appearance and graphics. You may not modify, reproduce or distribute the content, design or layout of the Website, or individual sections of the content, design or layout of the Website, without our express prior written permission. For media enquiries, please contact [email protected]

Sign-up to receive energy transition news and alerts of new podcast releases

View all the previous, current and future episodes of the Energy Transition Now podcasts.