As the world began recovering from the coronavirus, the UK saw an opportunity to “build back better”. The government launched a Ten Point Plan to spur investment in energy and low-carbon technologies, including hydrogen. It’s original 5 GW target for low-carbon hydrogen production by 2030 doubled to 10 GW following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This ambitious target will require clear direction and strong mechanisms to support the development of a hydrogen economy.

Westwood’s Atlas New Energies solution currently tracks 45 low-carbon hydrogen projects in the UK. If all the capacity starts up as planned, this would surpass the UK’s target; however, only a small number of demonstration-sized green hydrogen projects have thus far reached final investment decision (FID). All parts of an incredibly complex value chain must move together simultaneously, which is much easier said than done in a nascent market.

Advantages in blue and green hydrogen

The UK government is taking a twin-track approach, supporting both blue and green hydrogen production since it has advantages in both.

Although not carbon-neutral, blue hydrogen can scale faster relative to green because 1) grey hydrogen production technology (SMR and ATR) is already well-established, as is carbon capture which is required for blue hydrogen production, although the latter has not been proven at scale and 2) it is currently produced from refineries and, hence, there is an existing demand base and can benefit from large economies of scale. Blue hydrogen can, therefore, provide the UK with a route to decarbonisation in the short-to-medium term until green hydrogen is more readily available and cost-competitive.

Natural gas is the feedstock for blue hydrogen production. The UK has access to abundant natural gas reserves in the North Sea – 240 oil and gas fields are in operation, supplying 40% of the UK’s gas needs. The UK is highly dependent on natural gas use in critical applications such as power and heat for industry and homes; thus, not only is natural gas important for the UK’s energy security but it also represents a significant opportunity for decarbonisation.

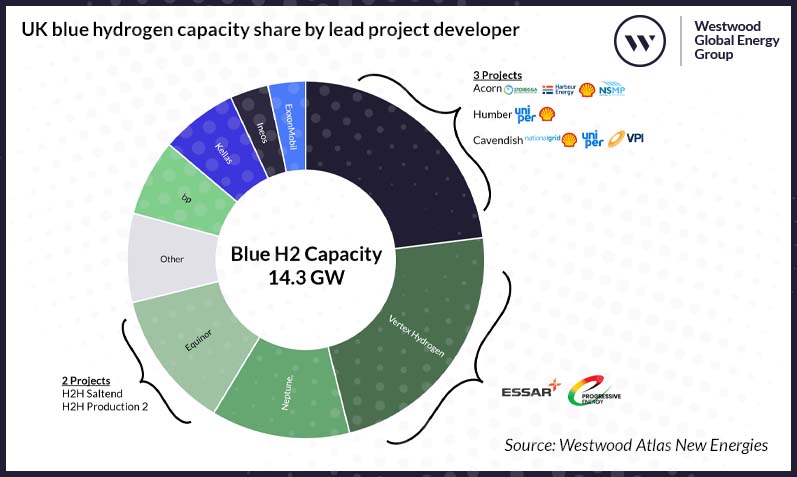

Blue hydrogen project development is being led by the large traditional oil and gas players, which demonstrates the importance of their role in the initial scale-up. These companies have access to existing hydrogen production (at refineries), natural gas supply and pipelines. They are also able to leverage their wealth of technical, geological and regulatory expertise needed to progress these projects.

UK blue hydrogen capacity share by lead project developer announced for start-up by 2030

Source: Westwood Atlas New Energies

Shell is the largest participant in the development of blue hydrogen projects in the UK; it is involved in three projects that will develop 3.3 GW. Vertex Hydrogen (a joint venture between Essar and Progressive Energy) is developing 3.3 GW through its Hynet project. Equinor is involved in two projects that together add 1.8 GW of blue hydrogen capacity. All the proposed blue hydrogen projects are coastal, which provides easier access to the necessary natural gas supply and CO₂ storage.

For green hydrogen production, the UK is surrounded by seas that boast some of the world’s best wind conditions, and its shallow seabed along its coastline makes offshore wind relatively accessible and cheaper to construct. Because of these geographic benefits and strong regulatory support, the UK has the largest pipeline of offshore wind projects globally.

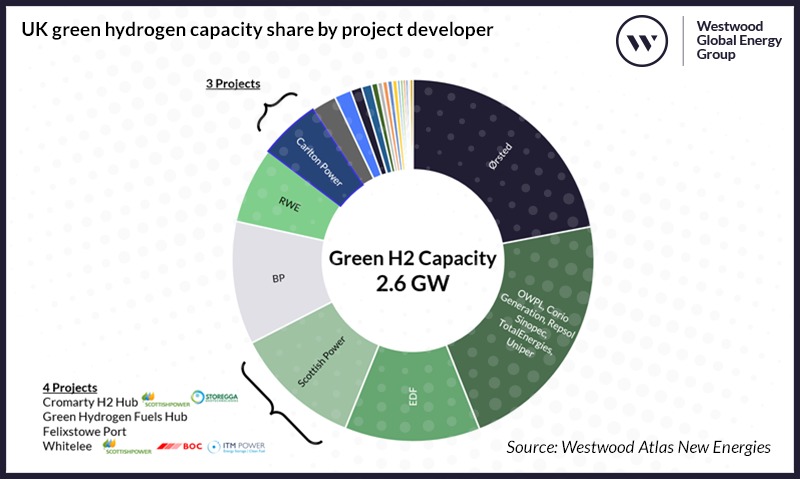

In contrast to blue hydrogen’s large project pipeline, announced capacity for green hydrogen in the UK only totals 2.6 GW. Green hydrogen production is much more fragmented, with smaller project sizes and a higher number of developers.

UK green hydrogen capacity share by project developer announced for start-up by 2030

Source: Westwood Atlas New Energies

The largest of these projects is Gigastack, the UK’s flagship green hydrogen project led by Ørsted, Phillips 66, ITM Power and Element Energy. The 571 MW project, located in South Killingholme, intends to demonstrate the deployment of large-scale green hydrogen production powered by renewable electricity from Hornsea Two – the world’s largest offshore wind farm. Phillips 66 will offtake the hydrogen as fuel gas for its Humber refinery. ITM Power will supply a 5 MW electrolyser for the demonstration, which it is hoping to scale up to a 100 MW electrolyser system.

The UK also has an advantage in the green hydrogen supply chain, as it is home to ITM Power, one of the world’s largest proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolyser manufacturers.

The UK’s geological formations are also a significant advantage as they can used for the storage of both hydrogen and carbon. The UK has one of the four salt caverns globally currently being used for hydrogen storage, but there is potential to convert more salt caverns currently used for natural gas into hydrogen storage. A handful of UK conversion projects are under planning and are expected to be online between 2025 and 2030.

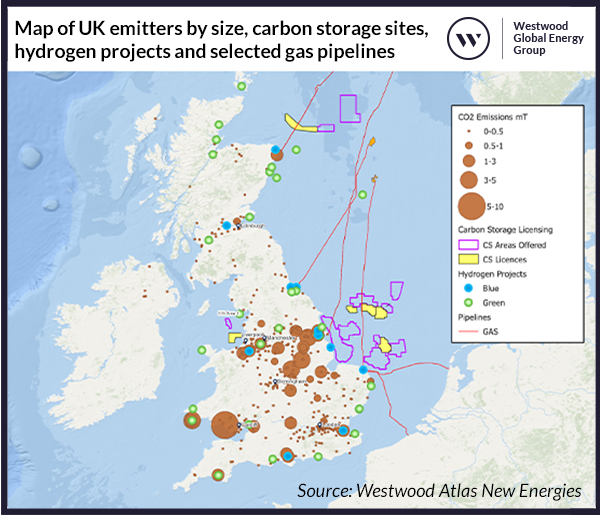

Carbon storage (CS) will be important to achieving industry decarbonisation and for the scale-up of blue hydrogen. The map shows the blue hydrogen projects along the UK’s east coast. The business case for these projects is strengthened by the fact that carbon storage is located relatively nearby, as the carbon captured during production can be easily transported and stored securely and cost-effectively. The UK will require 104 MTPA of CO2 storage by 2050 and it has at least 70 GT of offshore CO2 storage capacity – one of the largest in Europe.

Map of UK emitters by size, carbon storage sites, hydrogen projects and selected gas pipelines

Source: Westwood Atlas New Energies

Moving beyond the initial clusters

To help reduce costs, mitigate significant risk and provide greater certainty for early adopters and investors, hydrogen projects are being constructed close to demand centres in clusters, which in the case of the UK is in the industrial heartlands. The UK government plans to establish four industrial clusters by 2030. These clusters will be instrumental in the initial uptake of hydrogen because the projects within these clusters will receive the funding support required to make low-carbon hydrogen affordable.

Eventually, demand will move further away from supply, resulting in the need for a more extensive pipeline distribution network. Project Union is one such project. Spearheaded by National Gas, it aims to create a hydrogen backbone for the UK by repurposing 2,000 km of pipeline (25% of the UK’s natural gas transmission pipeline) to hydrogen. It will initially link the industrial East Coast clusters of Teesside and Humber but will look at connecting into the natural gas transmission network and into the Bacton gas terminal, which could open up hydrogen trade with Europe.

However, there is additional work to be done. There are other demand centres that exist outside of these clusters that also need to find a route to decarbonisation and are exploring what hydrogen means for them. It is this phase that needs further attention and government support.

Risks and uncertainties

While the UK is primed for success, much of this is down to the government. Undoubtably, the government has made great strides towards laying the foundations for a hydrogen economy, but there are still risks and uncertainties that need to be addressed. A few notable ones are around policy, competition, hydrogen definitions, business models and demand.

To qualify for government support, blue hydrogen projects need to come online by 2027, which means projects must take FID in 2024. Few are willing to assume the risk of a binding ‘Take or Pay’ contract that is usually required before FID takes place without further guarantees. The question is, how to overcome the ‘chicken and egg’ problem? One way would be for the government to offer non-binding initiatives to provide more certainty and encourage projects to move through to the next stage (front-end engineering and design).

In conclusion, the UK can boast of numerous advantages that could see it become a leader in the creation of a highly competitive and successful hydrogen economy. Whilst risks and uncertainties abound, these can be mitigated to secure investment – strong, clear, streamlined, and timely government policies will be key. As well, the incentives must permeate through all parts of an incredibly complex value chain. Competition is quickly heating up around the world and any delay or lack of clarity in the government’s steer could have adverse consequences for the UK’s hydrogen ambitions should investors believe they can obtain greater certainty and higher returns elsewhere.

Joyce Grigorey, Director – Hydrogen

[email protected]