ESG performance: just what are investors looking for?

Getting money from investors is never easy. And for the oil and gas sector, it’s getting harder. In a sign of the times, the UK Liberal Democrat party last month proposed banning new fossil fuel company listings from the London Stock Exchange. With the Lib Dems far from the halls of power, and new oil and gas listings fading, the proposal had more than a whiff of PR stunt about it.

But it underscored a growing problem for oil and gas: the industry’s core business model is no longer seen as compatible with responsible investing. This was already patently apparent in May, when ExxonMobil and Chevron were both hit by activist investor actions on the same day. That same month, the International Energy Agency—traditionally an oil and gas cheerleader—published a roadmap for net zero emissions by 2050 that called for a halt on all new exploration and production (E&P) developments.

E&P companies “need to prepare themselves for a world where exploration capital is constrained,” we concluded at the time. The same goes for the remainder of the oil and gas value chain.

Few leaders in the industry would now doubt that they must adapt. For companies looking to retain hydrocarbon assets, moving towards low-carbon operations (covering Scope 1 and 2) is now a minimum expectation. Investment and innovation will also be needed in carbon removal technologies and in carbon-free variants of current products for the industry to manage its future risk. Diversification into non-hydrocarbon areas such as offshore wind can also play a role. Adapting is an immense task, with each company likely having to develop a strategy based on its own set of circumstances.

A key question is: how far and how fast do I have to go to get investors back on board? The answer, unfortunately, is far from clear.

ESG and sustainable investing

Reticence to back oil and gas companies is born from wider investor concerns about environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance. With over half of the total funds managed now committed to a net-zero target, there is an increasing consensus that high ESG scores are linked to improved long-term returns. Furthermore, says the investment management behemoth BlackRock, “ESG is often conflated or used interchangeably with the term ‘sustainable investing.’ We see sustainable investing as the umbrella and ESG as a data toolkit for identifying and informing our solutions.”

However, recent evidence indicates this kit may house blunt instruments rather than precision tools. A study last month by the London, UK-based think tank InfluenceMap found most climate-themed investment funds, including those from State Street Corporation, UBS Group and BlackRock, are misaligned with the goals of the Paris Agreement.

“The lack of consistency and clarity makes it difficult for investors to determine what these funds’ descriptors mean in practice,” noted InfluenceMap analyst Daan Van Acker.

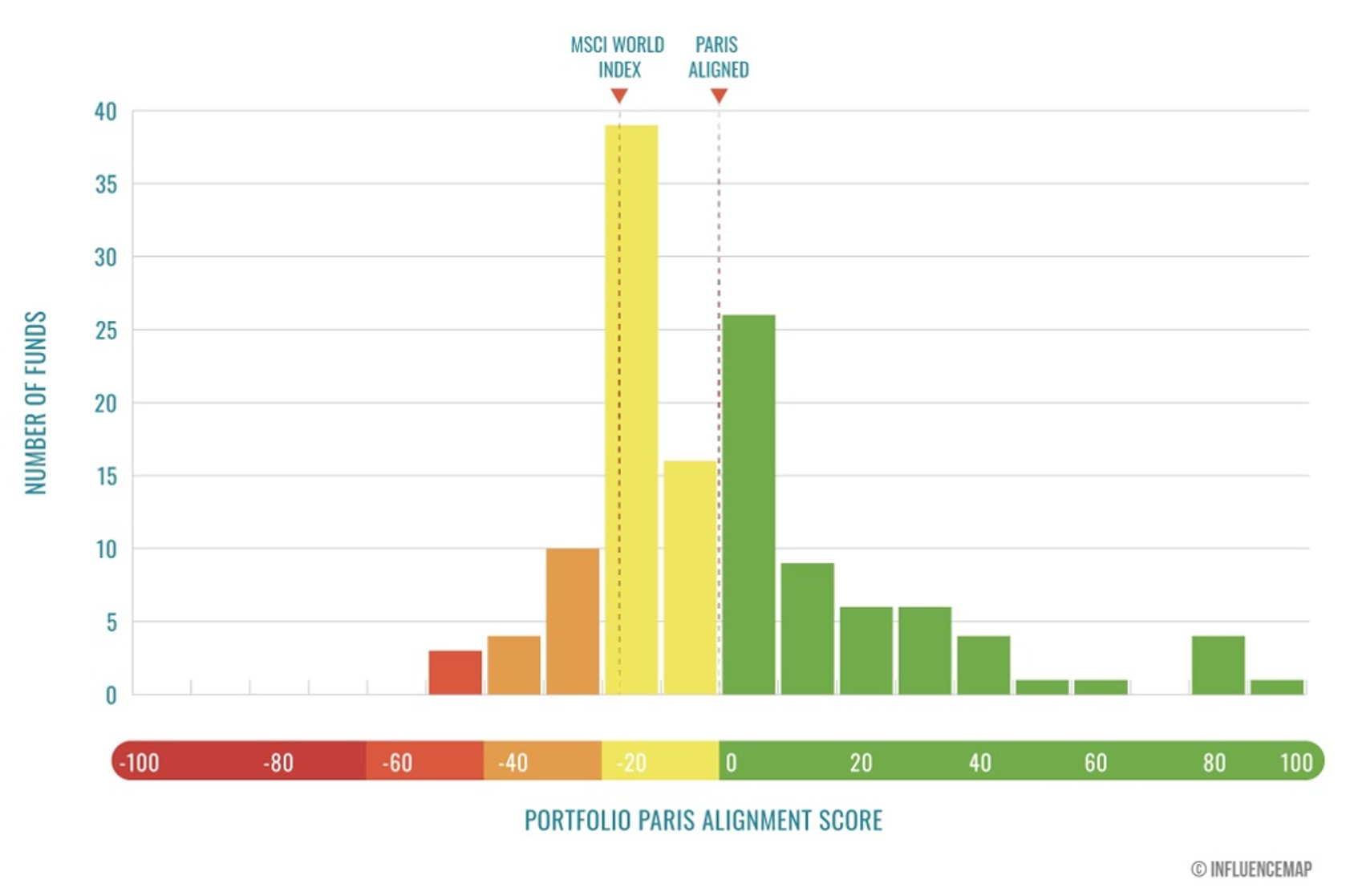

How climate-themed funds measure up against the Paris Agreement. Funds with scores below zero claim to be climate-focused but support investments that go against Paris Agreement goals. MSCI = Morgan Stanley Capital International.

Source: InfluenceMap.

This lack of consistency is not helped by the fact that there are many ways to measure components of ESG, resulting in confusion and a divergence of methodologies – and therefore ESG ratings – for individual companies. There are several tools and assessments, including those developed by the asset owner-led Transition Pathway Initiative and financial think-tank Carbon Tracker, for example, that use different methodologies to rank and benchmark companies’ relative preparedness for the transition to a low-carbon economy. And then there are the requirements of specific investors.

BlackRock, for instance, has gone from having 12 to 1,200 key performance indicators relating to sustainability related risks. And Kimmeridge, a private equity firm focused on making direct investments in unconventional oil and gas assets in the US, last year published a list of five sustainability requirements for its investment targets.

These include the elimination of routine flaring by 2025 and the reduction of US methane intensity below 0.2% of gas production by 2023. The good news is that “for the E&P industry, a low-carbon future does not mean abandoning or exiting the business,” said the firm. “Rather, it represents a world where companies operate more efficiently while measuring, reporting and minimising their impact on the environment.”

Clarity on the path ahead

Foreshadowing InfluenceMap’s research, in March BlackRock’s former chief investment officer for sustainable investing, Tariq Fancy, said: “The financial services industry is duping the American public with its pro-environment, sustainable investing practices.” And if investment managers themselves cannot make up their minds about what constitutes a sustainable business, how are oil and gas companies supposed to know what to aim for?

For a start, the financial services industry needs to be much clearer and consistent in what it expects from the oil and gas industry. Long-term goals, such as net zero, are helpful in setting a direction. But the oil and gas industry requires its financial partners and investors to be resolute and decisive, clearly articulating sustainability metrics and returns expectations, to help companies benchmark themselves and access capital in an efficient manner.

Reducing emissions and carbon footprints is an overarching theme that needs to be expounded using achievable objectives, metrics and goals over time. Given the circumstances of each oil and gas company, and the breadth of stakeholders involved in defining and communicating its future, it is also essential there is engagement and alignment across the board, management, investor relations, investors and financial partners on ESG and its implications. Having a good grasp of commercial and financial drivers along with the relative importance of different components of ESG will be crucial going forward.

The oil and gas industry needs to adapt if not transform its business in the face of the energy transition. As a capital-intensive industry, clarity from and alignment and active engagement with investors and financial partners will be key to achieving that.

We’re delighted to start announcing guests for our next series of Energy Transition Now Podcasts.

The digest: this month’s key headlines

- The Scottish government is calling for input into its latest Sectorial Marine Plan, which is due to target the decarbonisation of oil and gas through offshore wind. The plan will focus on “smaller innovation projects and projects targeting the electrification of oil and gas infrastructure.”

- Shutting the dirtiest 5% of power stations could cut electricity generation emissions by 73%, according to a study published in Environmental Research Letters. In case you’re wondering, the world’s most polluting plant in 2018 was the Belchatow coal station in Poland.

- Chevron has followed industry peers with the creation of a division dedicated to low-carbon investments in areas such as clean hydrogen and carbon capture. Former North America upstream oil exploration business head Jeff Gustavson is leading the New Energies unit.

- Decarbonisation targets could be under scrutiny after Australia’s Environmental Defenders Office filed a federal court case against Santos over the gas giant’s claims that natural gas is “clean fuel” and it has a credible pathway to net zero emissions by 2040.

- As floating platforms promise to harness wind farther from shore, a challenge is how to get the energy back onto land. The answer, according to Japanese firm PowerX, is the Power ARK 100: an automated vessel carrying 200 MWh of battery storage.

- Container logistics leader Maersk has said it will add eight carbon-neutral methanol-fuelled ocean-going container vessels to its fleet in the first quarter of 2024.