Energy Transition Insights

Clean hydrogen: today’s reality or tomorrow’s dream?

The level of hype surrounding clean hydrogen is so great it is not only hard to miss but also hard to keep up with. Last month, for example, the Portuguese government signed a memorandum of understanding with the European Investment Bank to help fast-track the deployment of 50 GW of green hydrogen capacity by 2050.

For comparison, that is more than five times the total cumulative solar capacity the country expects to have installed by 2030. And Portugal is not even considered a major clean hydrogen producer within Europe. The oil and gas sector should view such announcements with interest. After all, clean hydrogen—whether ‘blue,’ produced via steam methane reforming (SMR) with carbon capture and storage (CCS), ‘green,’ via electrolysis from renewable generation, or ‘turquoise,’ via methane pyrolysis—is potentially a major energy transition opportunity for the oil and gas sector.

Many of the principles involved in moving, storing and commercialising fossil fuels are directly transferable to hydrogen, and the oil and gas sector will ultimately need to transition to alternative fuels as pressure increases to reduce carbon emissions. And despite ongoing debate over the pros and cons of using hydrogen as an answer to many of the energy transition’s questions, there now seems to be little doubt over the future potential of clean hydrogen.

In February, more than 30 countries had national hydrogen strategies in place and more than 200 large-scale projects had been announced across value chain, with a total worth of more than $300 billion. That is around three-fifths of total upstream oil and gas investments in 2019—and clean hydrogen has not even taken off yet. However, the clean hydrogen market’s immaturity is arguably one of its most vexing features from an oil and gas perspective.

Sure, there is a big opportunity out there. But is it worth taking seriously at the moment? If you invest in clean hydrogen now, would you actually be able to sell any?

For a brief overview of why hydrogen is important to the energy transition, and what types of hydrogen there are, view the explainer page here.

A hard sell today

In theory, yes. A November 2020 paper by researchers from the Jožef Stefan Institute in Slovenia found that “green hydrogen is already competitive in the field of transport, as long as its sales price is not burdened with additional environmental taxes, as is the case with other fuels.”

However, the study looked at green hydrogen produced from hydro energy, which has extremely low costs and a high capacity factor. And while green hydrogen under this scenario may be competitive with today’s ‘grey’ product, which is created via not-so-clean SMR, the transportation market is not exactly begging for the gas at the moment.

Despite predictions a decade ago of millions of fuel-cell vehicles on the roads today, as of the end of 2019 there were only a little over 18,000 hydrogen-fuelled cars and trucks around the world. The outlook for fuel-cell vehicles remains bullish, not least because it may be hard to fully electrify heavy road transportation.

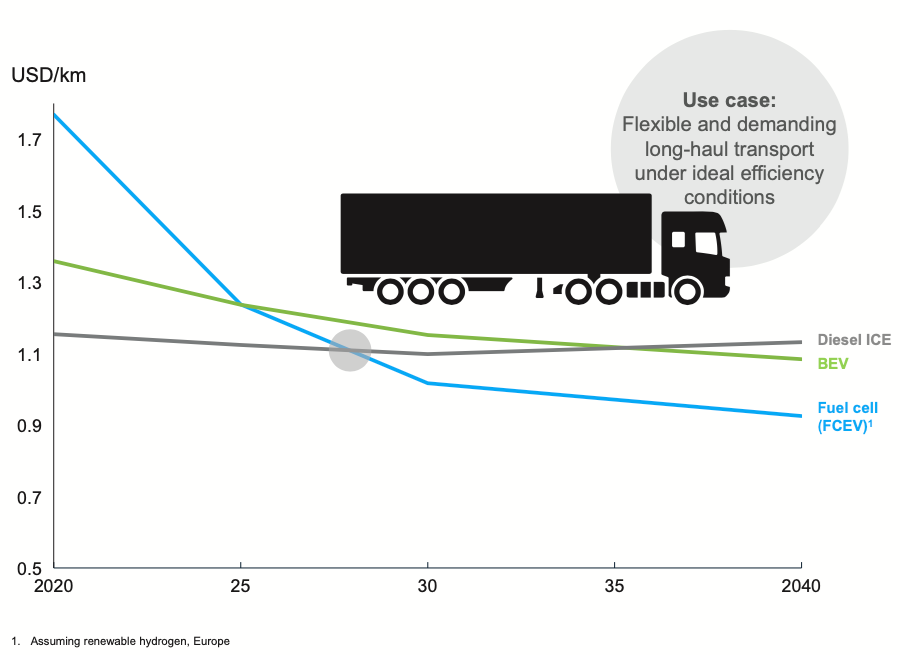

Total cost of ownership of on-demand heavy-duty truck with various fuel types. Source: Hydrogen Council/McKinsey & Company, Hydrogen Insights Report 2021.

Total cost of ownership of on-demand heavy-duty truck with various fuel types. Source: Hydrogen Council/McKinsey & Company, Hydrogen Insights Report 2021.

But even industry body the Hydrogen Council does not see the total cost of ownership of fuel-cell-based heavy-duty trucks beating diesel before the late 2020s. And other sources, such as the Energy Transitions Commission, note that this market could in part potentially be better addressed through electrification.

Episode 1 of the Energy Transition Now podcast, featuring Sustainability Consultant William Day, now available.

Transportation is not the only potential market for clean hydrogen, of course. One area that multiple sources claim has early potential is the development of ‘hydrogen hubs’ where production is located next to demand centres, for example at ammonia manufacturing plants and refinery operations. The reality, though, is that there is still little clarity over which segments will be the biggest early adopters of clean hydrogen, which muddies the waters when it comes to identifying potential near-term markets.

Similarly, there is little agreement on how the costs of different colours of hydrogen will evolve. There is already a wide range of estimates for the cost of different hydrogen types, with KPMG reporting a range of roughly USD$1 to $2.50 per kilo for grey, $1.50 to $4 for blue and $2.50 to $6 for green. Furthermore, cost reduction estimates are complicated because the economics of clean hydrogen is subject to multiple variables, from carbon pricing (which could make grey supplies more expensive) to renewable energy costs (which could make green supplies cheaper).

These variables are changing over time and are also strongly dependent on geographical markets. Australia is being mooted as a prime location for green hydrogen production, for example, because its immense solar and wind resources could offer large-scale low-priced renewable electricity. Another factor that strongly influences clean hydrogen’s outlook is the scaling of supply and demand. This will help bring down the cost of CCS and electrolysers on one hand and fuel cell technology on the other.

The Hydrogen Council estimates that around 65 GW of electrolysis capacity will have to be installed to bring about the cost reductions needed for green hydrogen to be competitive with grey. That “implies a funding gap of about $50 billion for these assets,” the Council says.

Clean hydrogen proponents might argue that such funding is likely to be readily available given the governmental targets cited above. But the Hydrogen Council notes that only $80 billion of the $300 billion in commitments so far can be considered ‘mature,’ as “in a planning stage, has passed a final investment decision, or is associated with a project under construction, already commissioned or operational.”

Furthermore, notes a March 2021 paper from the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, “While it is relatively straightforward to publish a document setting out a strategy, it is likely to be significantly more challenging to put in place the required budgets, incentives and regulatory structures.”

The bottom line is that while targets abound, in practice there is still little clarity over how clean hydrogen will be rolled out at industrial scale.

Build your strategy now

Does this mean oil and gas companies should give clean hydrogen a miss for now and check back in once the market has matured around 2030? Not at all. A survey last year found the majority of energy companies are already investing in clean hydrogen. While the outlook for clean hydrogen is hard to assess with certainty, what is already clear is that there is considerable governmental and institutional interest in getting things done.

The prospects for the market are evolving rapidly, and even if it ends up at the lower end of expectations the potential is significant. Some observers believe clean hydrogen’s impact on regions such as Scotland could be as big as that of North Sea oil and gas. And perhaps most significantly, the barriers to entry at present are very low. With few projects on the ground, to paraphrase Woody Allen, 90% of getting into the hydrogen economy is showing up. As a result, oil and gas companies should take the following approach to the clean hydrogen market:

- Track the evolution of the market to understand how it is developing.

- Participate by joining relevant groups and organisations.

- Map potential clean hydrogen ecosystem opportunities to existing skills and service capabilities.

- Test capabilities and synergies within pilot projects where possible.

- Gauge when it makes sense to commit significant investment to emerging clean hydrogen opportunities.

Remember that our commercial advisory service can help you develop an energy transition strategy suited to your business. For more information, get in touch.

The digest: last month’s key energy transition headlines

- US President Joe Biden declares this is a ‘decisive decade’ to deal with climate change.

- Lundin Energy claims world’s ‘first certified carbon neutrally produced oil.’

- Bloomberg: Divesting assets is no good for the planet if new owners carry on drilling.

- Saudi Arabia joins America and others in effort to help oil and gas meet Paris Agreement

- Liquefied natural gas is out of the running as a future shipping fuel, the World Bank says.

- Someone is failing to report carbon emissions the size of America’s.

- Oil and gas pipelines are bigger carbon polluters than coal plants, study shows.

- Geothermal energy is gaining renewed traction as low-carbon baseload power.